The Problem With Loyalty Coalitions is the Word "Loyalty"

I'm going to get a lot of s*** for this essay

I promised I was going to write a shorter essay this week and then I fixated on this topic (that I’ve *been* fixating on, honestly) and tried to write about other things that would have been a) shorter and b) caused me less mental stress but kept coming back to this subject so, here we are.

In this essay, I discuss why multi-brand loyalty programs don’t work (and in my opinion, never will) (cue the angry Twitter (X?) mob).

Meanwhile, in this week’s Hot (Girl) Links we’re talking about modern-day mating calls and what makes something counter-culture cool vs. just counter-culture (with no real conclusion, truthfully). Enjoy! I’ll be on Twitter waiting.

I have spent a lot of hours, and a lot of brain power, thinking about multi-brand loyalty programs, or loyalty coalitions as I’ll refer to them from here on. My relationship with the idea has evolved, and not necessarily for the better. I used to be their biggest cheerleader, thinking that this was something web3 could enable that consumers wanted and ultimately brands would too (despite their fraught history with them).

Now, I realize, loyalty coalitions will never work. The problem, however, is not what you might think. It lies with the concept of “loyalty” itself.

The tl;dr is this —

Loyalty coalitions have failed repeatedly because participating brands feel they are giving (brand value) more than they are getting — and are losing (hard-earned loyalty consumers) to other competitive brands. This is always going to be a negative value proposition.

The solution to this problem lies in ditching the word “loyalty” altogether.

The biggest problem brands face today is customer acquisition and retention. These coalitions should instead reposition them as ‘new customer acquisition funnels’, providing a single ecosystem token that consumers can “earn” via engagement, and spend on brands they love — thereby enabling status and discovery (the true consumer desires).

That’s the ‘too long, didn’t read’ version. But if you’re like, not long enough, need to read… Please continue (and I love you!):

What is the Point of a Loyalty Coalition, Anyways?

Before exploring why loyalty coalitions haven’t worked, I think it’s important to explore why they are, ostensibly, a great idea — and why it’s been tried so many times. To summarize:

Consumers Want —

Status: They want brands to recognize their status as a consumer, whether they are a repeat shopper or a first-time customer — and be treated appropriately and personally.

Discovery: Consumers want to discover new brands they might like that are similar to those they already shop, and immediately receive delightful perks, discounts, etc. without necessarily waiting to achieve status.

They want to have their cake and eat it too, basically. Who can blame them?

Brands Want —

1. Customer Acquisition and Retention: Brands want to reward their loyal customers while also acquiring customers from other brands with similar target consumers at a low-cost with little intent.

So Why Haven’t They Worked in the Past?

The coalition loyalty space is a graveyard haunted by the ghosts of companies big and small who have tried — and failed — to get brands to cooperate in a single interoperable loyalty ecosystem. The most successful case was Plenti, who made it 3 whole years before shutting down.

What has gone wrong?

Not Enough Curation — And Thus Not Enough Value

Many Loyalty Coalitions (LC’s) have abided by the ‘bigger is better’ mentality and thus attempted to onboard any and all brands. With a lack of thoughtful curation, and therefore little synergy or overlap, consumers struggle to spend the points they end up accruing.

I believe that LC’s should lean in and curate brands by industry vertical — Like Sephora has done with beauty and Blackbird is doing with restaurants. However, this leads to its own set of problems:

2. *Too Much* Curation — And Direct Competition

The reason many LCs fail is because many brands from the same industry will join, and ultimately feel that they are losing hard-earned loyalty users to their direct competitors. This is obviously going to feel like a negative value proposition. (This doesn’t have to be the case, which I explain below).

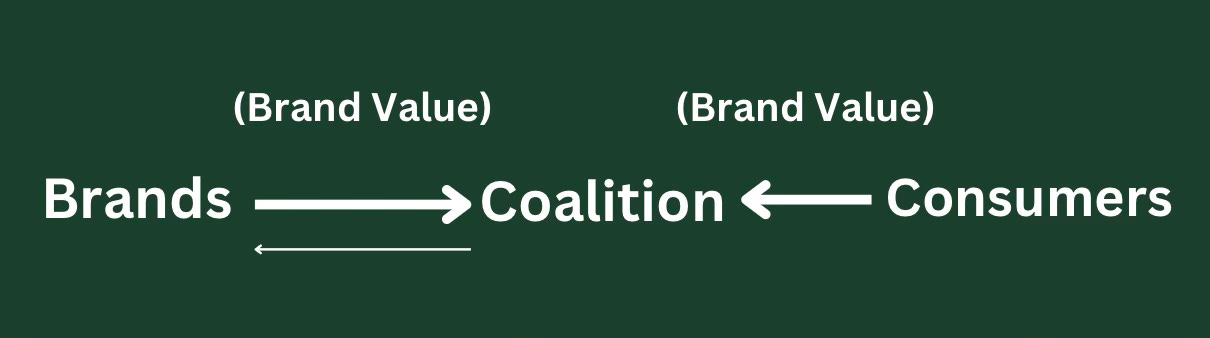

3. Whose Brands Boosts Whose? A Push and Pull Effect

Inherent in any LC is a constant struggle for brand value and loyalty. The value of an LC is almost directly proportional to the value of the participating brands. The participating brands, in turn, feel (and justifiably so), that they are propping up the brand value of the LC. To add insult to injury, the participating consumers in the LC end up feeling brand allegiance to the *LC*, rather than the participating brands. This is a lose-lose situation that looks a little like this:

Now, you might be thinking, what about airlines! And credit cards! Those are the exception, not the rule (if you have watched He’s Just Not That Into You you know what I’m quoting right now). And you are falling victim to survivorship bias.

Why Loyalty Coalitions Work For Airlines and Credit Cards (🙄)

Survivorship bias is when you pay attention to the 2 times something has worked rather than the 2M something has failed as proof that it has legs. This is that. But to indulge you —

Airlines: Coalition loyalty works in industries where a single company cannot, by the laws of physics or just laws, generally, service a whole industry. In these cases multiple companies must all service various parts of the industry, and thereby benefit from an interoperable loyalty program.

Credit Cards: Credit cards have the advantage of a) tracking your spend across multiple brands (which most CL’s cannot do) and then b) rewarding those dollars spent with points which are, effectively… more dollars. These extra dollars then get spent back on brands. This is just a net-positive for brands, but not true of most CLs.

Loyalty-Point Exchanges Are Not the Answer

I’m sorry I even have to address this, but twitter thought leaders with their multiple threads on loyalty point exchanges are forcing me to.

In case you don’t live on Twitter like I do (good for you, tbh), a loyalty point exchange would allow users to ‘swap’ their points and benefits for others from other brands, occasionally supplementing an exchange rate with pure dollars spent (thereby effectively purchasing loyalty benefits). This is wrong for many reasons, including:

Erodes the Status of Loyalty: It feels pretty obvious that paying for a true ‘loyalty’ benefit erodes the value of having earned said loyalty.

The Inevitable Hierarchy: Inherent in the creation of a point exchange, is an exchange rate. This, by definition, directly compares and contrasts brands and creates a hierarchy in which one brand is considered ‘stronger’ than another. Ie. 5 points of brand X is worth 4 of brand Y. Or $1 USD is currently 143 Japanese Yen (yes, really). Same thing.

Simple Logistics: The simplest answer as to why these won’t work is just… logistics. Imagine trying to create the aforementioned exchange rate for every type of loyalty point, benefit, perk etc. that could exist, and allowing users to subsidize exchange rates with $ spent. I feel tired just thinking about it.

What’s in a Name: Reframing ‘Loyalty Coalitions’ as ‘Customer Acquisition Communities’

… Or something like that, but a lot better.

By definition, using your loyalty points and spending them on a different brand is not loyalty. For that reason, none of the above ideas concerning LCs or loyalty exchanges will work. So let’s take a step back, and reframe.

Reframe, specifically, to the idea of a customer acquisition funnel.

To revisit why LCs don’t work — They feel that they bring value to the LC brand rather than the other way around, and lose hard-earned loyalty consumers to competitive brands.

Ultimately, LCs want customer acquisition and retention, and consumers want status and discovery.

This can be achieved with what I am calling the ClassPass Approach.

The ClassPass Case Study

At launch, ClassPass, a subscription pass for boutique fitness classes, faced the classic marketplace cold-start problem: They needed both fitness studios and consumers on board, but both necessitated the other. ClassPass founder Payal Kadakia found a way around this.

Kadakia recognized that studios were already giving away free classes to attract new clients. So, she packaged 10, and consumers paid $49.99 for the convenience. This was enough of a value prop to attract a *paying* community of users. Once the users were on board, of course, the brands quickly followed. ClassPass provided a new customer acquisition funnel to these studios, full of consumers who wanted to discover new studios without committing to a full membership.

Eventually, ClassPass launched credits, which users could purchase and spend on classes, with studios pricing their classes as they saw fit. So while one studio’s class might cost 5 credits, another might only be 3. The brands, to further attract the community, provided fun extra perks, benefits, etc.

How Does This Apply More Broadly? What is the ClassPass Approach?

This case study illustrates the best way (IMO) to build a customer acquisition ecosystem with a single token — with a few changes that I’ll highlight below:

Package Pre-Existing Perks to Create an Initial Value Prop: Package perks and benefits *already offered by companies* (like the free workout classes) to create an initial value prop and onboard a community.

Use the Community to Onboard Brands: Once you’ve built the community, you can more easily convince companies to onboard to the marketplace by presenting a customer acquisition funnel.

Introduce an Ecosystem Token: Once the community and brands are on board, introduce an ecosystem token.

Allow Users to *Earn* the Token: This is where I deviate from ClassPass — I believe a better approach is to allow users to “earn” the tokens (rather than purchase them, via actions on behalf of the brand (Ie. Creating UGC, sharing products, etc.)

And Spend Them on Perks, Benefits & Products: I strongly advise that these communities focus on benefits other than simply discounts, lest this become another GroupOn (discounts cheapen brands).

Enabling Pricing Flexibility: Allow the brands to price their benefits in the ecosystem tokens as they see fit. This allows for an extension of their typical pricing strategy.

This approach satisfies the brand & consumer checklist:

Brands are *gaining* new consumers, not losing loyalty consumers. In addition, the brand value comes from the community — not just from the participating brands. As such, brands get as much as they give.

Consumers can gain status on this new platform, and receive the appropriate treatment from every brand the interact with. In addition, they can discover new brands that align with their tastes, without having to commit to the brand from the start.

Why is This Better in Web3?

This obviously does not *need* web3 to exist, which is evidenced by the fact that ClassPass exists. I do believe, however, that web3 makes this better for the following reasons:

Engage-to-Earn: The single biggest difference in my version of the ClassPass approach is that I believe these ecosystem tokens should be ‘engage to earn’ rather than purchased. This creates a higher-value consumer who has more ‘skin in the game’.

Wallet Access: In putting the tokens on-chain, these coalitions gain access to consumers wallets, which contains extremely valuable psychographic information that brands currently can’t access/see. Ie. What other communities they are a part of, what other ‘digital assets’ they’ve purchased, etc. (This is especially true in the future when *everything* on the internet is an NFT! Like the dress you bought on Farfetch last week, for instance.)

Anyways, the tl;dr is that, after much trying — I think we need to accept that multi-brand loyalty programs are inherently flawed, but repositioning them as ‘new customer acquisition’ funnels using the ClassPass approach can provide the same benefits to both brands and consumers, and be lucrative for whoever starts it as well. Free ideas people. Thank me later. :)

HOT (GIRL) LINKS

Silencio Opens a New Location in New York

… Uptown. Not just uptown. To quote the Dazed reporting on the opening, specifically “Located in Hell’s Kitchen, a stone’s throw from NYC’s Times Square.’ In truly any other instance, those 11 words would be an instant death knell. I genuinely can’t think of a worse description of a location. But it made me wonder — what is the difference between counter-culture cool, and just counter-culture? When does behaving outside the norm attract consumer behavior and when is it… Just too outside the norm?

I have no answer, but I do have thoughts. Perhaps, every ‘anti-establishment’ group, scene or movement still has non-negotiables. In New York, I could argue that a non-negotiable is traveling too far — Ie. Basically anything above 25th street or past Bushwick Ave. And don’t even try to do anything in NJ. This automatically renders something as counter-culture … not cool. I discussed with a friend of mine, however, and she pointed out great exceptions, including the Russian Samovar, Habibi, or even Casa Cipriani honestly (it’s downtown but far af). Is it perhaps the social personalities associated with these places that drive crowds to these places, despite their locations? In that case, will Silencio be able to succeed no matter where they are? Why not just base themselves in the LES like a normal cool club? (I ask, selfishly)

I am not the first person to ask this question nor am I even close to the most eloquent but all I really want to know is whether I should trek my ass up to W 57th Street.

Anyways this is also relevant because I was just at the original Silencio in Paris on Tuesday for the 3rd annual Future Fashion Summit. The takeaways? The future is definitely phygital, my friends.

Hot Wheels? More Like Hot Lips — Charlotte Tilbury Partners with the F1 Academy

You like what I did there? Honestly, this marketing campaign is genius. Ever since the launch of Netflix’s Formula 1 docuseries Drive to Survive launched in 2019 (the worst thing to happen to the sport according to my Greek BF), female viewership is now 40% (up from 8% in 2017) (Greek BF also did not believe this stat). I can believe it, however, as every weekend during the season I’m subjected to girls’ Instagram stories about Max Verstappen and Daniel Ricciardo which I swear is just a thinly veiled modern-day mating call.

Anyways, rant aside, Charlotte Tilbury is the first truly female consumer-focused brand to sponsor *any* Formula 1 car which, if the stats are not a lie like the BF thinks they are, is a very strategic move. The academy is not as widely viewed/known, to be sure, but Charlotte Tilbury hopes to help support only the 3rd woman ever to reach the top F1 division — and they’ll be right there when it happens. I am very “for the girls” and what not, but will personally be cheering for Carlos Sainz.

Sephora Launches Sephora Universe (In Beta)

2021 called and they want their headline back? Not to be rude but it feels like maybe Sephora started working on this project peak “metaverse” and then it took so long to complete that it carried them right into a bear market where no one wants to *hear* the word metaverse… Let alone spend time in one. Sorry, that definitely was rude. Let’s give them the benefit of the doubt. There are a couple reasons I can imagine this being interesting:

The best kinds of consumer products take advantage of a major technological shift — and Apple’s Vision Pro is absolutely that. Maybe Sephora Universe is launching right on time to take advantage of a VR experience!

It’s impossible to ignore Roblox user statistics (another digital world). With 70M DAUs and 216M MAUs, kids are clearly spending obscene amounts of time there. Doing what? That’s anyone’s guess, but maybe Sephora knows the secret.

I’m out of reasons but I work in web3 so who am I to say anything negative, really. Let the people earn digital beauty collectibles!

LVMH is Creating Their Version of “The September Issue”

This is a slightly niche subtitle but I just finished reading Amy Odell’s biography of Anna Wintour (Anna). In it, she recounts the making of The September Issue in 2007, the iconic documentary that launched Grace Coddington to fame (rather than Anna — who was, to be fair, very graceful about it apparently). This film helped attract enough brand growth for Vogue that they managed to stay afloat following the 2008 financial meltdown (It was released in 2009). Another easy comp is what Drive to Survive did for Formula 1, as we discussed above. LVMH obviously sees the value (er - necessity) of entertainment, and has created 22 Montaigne Entertainment, designed to explore film & TV opportunities across its 70 Maisons. I, personally, vote for A Day in the Life of Bernard Arnault (I love him? Can you blame me? Weird? Maybe) or literally anything about Jonathan Anderson (maybe including his costume design for Challengers?). Bernard, if you’re reading this, I’m available for consulting services.

Kofferbuch

There is, apparently, a German word for a book that you pack in your suitcase with the intention of reading on your trip, but never do. Anyone who knows me knows I am prone to packing upwards of 7 books for *any* length of vacation. My ambition knows no bounds. My reality, however, is very bounded. This picture is from 2019 but could be from today (with a few title swaps).

Aleksia, loyalty isn’t dead — it’s just been misunderstood. The failures of loyalty coalitions aren’t evidence that loyalty is flawed. They’re evidence that we need better infrastructure to make it work. It just needed a better foundation and we’re building it.

Would love to connect to show you how. eduardo@perkss.io

Loyalty coalitions for brands is the dumbest idea on earth and it's sad you even had to write this - honestly. I personally also don't think a central token works because it creates the same problem of "why is a consumer earning points from brand A to spend on brand B". There's just no reason for it. The benefits of Web3 you mentioned work but I reckon and ecosystem token is unnecessary. You can build the contribution/engagement mechanic in better and simpler ways from the builders perspective, the brands and the consumers perspective.